"... Anglophone readers were starting to catch up, as a torrent of great work arrived intranslation, confirming Krasznahorkai’s mastery: 'Seiobo There Below' (2013), 'Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming' (2019), and, most recently, 'Herscht 07769' (2024), probably the most accessible of his novels. (All of the recent fiction has been rendered in fluid,sinuous English by the superb Canadian translator Ottilie Mulzet.) Each is an extraordinary and singular work, and each expands Krasznahorkai’s range."

"... Anglophone readers were starting to catch up, as a torrent of great work arrived intranslation, confirming Krasznahorkai’s mastery: 'Seiobo There Below' (2013), 'Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming' (2019), and, most recently, 'Herscht 07769' (2024), probably the most accessible of his novels. (All of the recent fiction has been rendered in fluid,sinuous English by the superb Canadian translator Ottilie Mulzet.) Each is an extraordinary and singular work, and each expands Krasznahorkai’s range."  "II was also mesmerized by 'Eye of the Monkey,' a new novel by the Hungarian poet Krisztina Tóth about love and death in an unnamed autocracy. She describes how the more baffling and absurd everything gets, the more people cling to the scraps they can control: 'His habits, routes, movements were a handhold; without them, he might lose his sense of orientation completely.'"— Jennifer Szalai, 'Our Book Critics on Their Year in Reading', The New York Times"In an unnamed Central European country, scarred by a civil war and buckling under an autocrat, citizens are deeply segregated by class and constantly surveilled. But the machinations of the United Regency, as the government is called in this novel, are hardly the focus; instead, the story traces the lives and travails of a handful of characters, including a psychiatrist who seduces his patient, as they confront dead-end choices. Tóth is an acclaimed Hungarian writer and has written one of the most elegant, disorienting novels I’ve read this year: It’s funny and evenhanded enough that the finale arrives as a devastating fait accompli. And Mulzet’s translation is feverishly good."— Joumana Khatib, 'Our Favorite Hidden Gem Books of 2025' , The New York Times"Novels that take on this assignment (Many characters! Many walks of life! A tortuous chronology!) tend to end up dissipated and confusing. Remarkably, Toth manages to hold our focus as the story forks in controlled, if mysterious, ways. A book that can be snaking and labyrinthine without sprawling aimlessly is — like an author who can handle elusiveness without opacity or coyness — quite a rare thing.

"II was also mesmerized by 'Eye of the Monkey,' a new novel by the Hungarian poet Krisztina Tóth about love and death in an unnamed autocracy. She describes how the more baffling and absurd everything gets, the more people cling to the scraps they can control: 'His habits, routes, movements were a handhold; without them, he might lose his sense of orientation completely.'"— Jennifer Szalai, 'Our Book Critics on Their Year in Reading', The New York Times"In an unnamed Central European country, scarred by a civil war and buckling under an autocrat, citizens are deeply segregated by class and constantly surveilled. But the machinations of the United Regency, as the government is called in this novel, are hardly the focus; instead, the story traces the lives and travails of a handful of characters, including a psychiatrist who seduces his patient, as they confront dead-end choices. Tóth is an acclaimed Hungarian writer and has written one of the most elegant, disorienting novels I’ve read this year: It’s funny and evenhanded enough that the finale arrives as a devastating fait accompli. And Mulzet’s translation is feverishly good."— Joumana Khatib, 'Our Favorite Hidden Gem Books of 2025' , The New York Times"Novels that take on this assignment (Many characters! Many walks of life! A tortuous chronology!) tend to end up dissipated and confusing. Remarkably, Toth manages to hold our focus as the story forks in controlled, if mysterious, ways. A book that can be snaking and labyrinthine without sprawling aimlessly is — like an author who can handle elusiveness without opacity or coyness — quite a rare thing. "Ugly coats, invisible elephants and giant monuments having sex with the clouds: Istvan Vörös' new novel manages to outdo the subconscious."— Mathilde Montpetit, The Berliner

"Ugly coats, invisible elephants and giant monuments having sex with the clouds: Istvan Vörös' new novel manages to outdo the subconscious."— Mathilde Montpetit, The Berliner "Much of Beyond the Cordons can be read as a lyric enactment of these ideas. 'Private and political pathologies overlap,' he writes in 'Eyes Turned Inside Out.' (Note, beyond this line’s programmatic statement, the compelling translation: The repeated p consonants form a halting, incendiary music, carried within the poem by a percussive and unstable meter, that together express themes of personal and political disruption within the endless instability of history. This poem was translated by Mihálycsa, but its attentive, sonic skillfulness is characteristic of both her and Mulzet’s translations throughout the volume.)

"Much of Beyond the Cordons can be read as a lyric enactment of these ideas. 'Private and political pathologies overlap,' he writes in 'Eyes Turned Inside Out.' (Note, beyond this line’s programmatic statement, the compelling translation: The repeated p consonants form a halting, incendiary music, carried within the poem by a percussive and unstable meter, that together express themes of personal and political disruption within the endless instability of history. This poem was translated by Mihálycsa, but its attentive, sonic skillfulness is characteristic of both her and Mulzet’s translations throughout the volume.) ♦ Shortlisted for the 2025 EBRD Literature Prize♦ Finalist for the 2024 National Book Critics Circle Gregg Barrios Book in Translation Prize ♦ Finalist for the Cercador Award, 2024♦ Washington Post 50 notable works of fiction from 2024"In a single sentence that sprawls out over 400 pages, Krasznahorkai tells the story of a Bach-obsessed gentle giant who unknowingly consorts with a gang of neo-Nazis. The surprisingly readable results offer a timely warning about our impotent slide into authoritarianism."♦ The TLS Books of the Year 2024"There simply isn't another writer like László Krasznahorkai, whose Herscht 07769 (Tuskar Rock), translated from the Hungarian by Ottilie Mulzet, is a single sentence amounting to some 400 pages and telling of Florian, a man who is convinced that all physical matter is on the brink of extinction and who initiates a one-sided conversation with Angela Merkel in a vain attempt to stave off apocalypse, all the while living at the beck and call of 'the Boss', the head of a neo-Nazi gang and a zealous devotee of Bach who has become maddened by attacks on statues of the composer throughout Thurginia - the plot, if you can call it that, so far out on the horizon of realism, with characters whose passions and obsessions are exposed so nakedly, that the novel, but the best of Krasznahorkai, takes on the cast of a sinister fable, it's sentence rushing headlong over a cliff, into a void." — Michael Lapointe"The form is demanding (it’s a single 400-page sentence), but Krasznahorkai’s latest is worth every moment of concentration. At the center of the narrative is Florian Herscht, a gentle giant with an intellectual disability who’s being exploited by a neo-Nazi gang leader. What makes this so exciting and satisfying is the author’s clear-eyed and open-hearted exploration of conspiracy thinking and nationalism, and the divisiveness they fuel."Editor's Choice: Seven New Books We Recommend This Week: "The protagonist of this feverish novel, a hulking man-child living in what used to be East Germany, writes pleading letters to Chancellor Angela Merkel imploring her to use her physics background to prevent a pending apocalypse. Beneath that improbable surface, the novel — which unspools in a single breathless sentence, rife with detours and digressions ably navigated by the translator Ottilie Mulzet." — The New York Times"In the abstract, his artistry may sound forbidding to all but the most devoted lovers of the European art novel. In concrete terms, though, Krasznahorkai’s work offers, to a degree rare in contemporary life, one of the central pleasures of fiction: an encounter with the otherness of other people. He’s a universalist cut loose from the shibboleths of humanism. And if 'Herscht 07769' doesn’t quite reach the heights of his masterpieces — 'The Melancholy of Resistance,' 'War & War' and 'Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming' — it may be the most accessible entry point so far to his visionary oeuvre.”—Garth Risk Hallberg in The New York Times" In a long book with only one terminal punctuation mark, not easy to read but graced by a certain poetry, Krasznahorkai allegorizes globalism and nationalism, gets in digs at complacent burgers and ardent environmentalists, and illustrates, through Florian and other characters, how thinly the veneer of civilization lies atop a thick crust of savagery. Brilliant, like all of Krasznahorkai’s books—and just as challenging, though well worth the effort required.”—Kirkus Reviews"'Apocalypse is the natural state of life,' Florian writes to Merkel, a line that doubles as an artist statement for Krasznahorkai’s brilliantly cacophonous novel, which conveys the sense that the end is already here, and that the trappings of civilization are easier to scrape away than paint from stone. This stands with Krasznahorkai’s best work.”—Publishers Weekly, starred review"The novel is over 400 pages but contains only one sentence, brilliantly translated by Ottilie Mulzet. It flows on and on in rhythmic phrases that absorb and enchant, sweeping us into a river of prose that is as captivating as it is disturbing. Herscht 07769 is a powerful portrayal of the dangers of nationalism and how fear rots a society from inside. It’s also a shattering story of violence and revenge and one person’s valiant if doomed attempts to change the world." — Rebecca Hussey, Judges’ appreciations for the six finalists of the National Book Critics Circle’s Gregg Barrios Book in Translation Prize"The syntactical flow is so potent it can rely on a simple comma for a major transition; it slips in and out of dialogue or violence, those more jagged rhythms, without losing cumulative effect. Such a style isn’t unique to Krasznahorkai (see William Gaddis, The Recognitions), but few writers have carried on so undaunted or shown such dexterity. Amid vast blocks of unbroken prose, action and desire develop with remarkable clarity, and there’s no mistaking the tonal shifts into threat or seduction⎯subtleties that, in English, bear out the heroic efforts of his translators, the latest the award-winning Ottilie Mulzet." — John Domini in Brooklyn Rail"... it’s like parting a curtain and stepping into a slow tornado of images, ideas, thought patterns whirling and elliptical, ever transforming, misdirecting, stuttering, stumbling through cascading potential pathways jutting out in every direction—it’s like stepping into a river and becoming a paper boat, floating down a river that commands your movement with its currents, here poetically rendered by Ottilie Mulzet’s translation, and Krasznahorkai is that river, conducting the movement of attention, the direction of the sentence, the meticulously plotted introductions of information, character, setting, conflicts”—Christopher Riggs in Asymptote"And yet that book — “Herscht 07769,” by the Hungarian genius László Krasznahorkai — is neitheran experimental stunt nor a pretentious folly. It is, instead, an urgent depiction of ourglobal social and political crises, rendering our impotent slide into authoritarianism withcompassionate clarity. It is also a book whose timeliness derives precisely from the wayits unusual style disrupts the ordinary literary mechanics of time... In all of this, Krasznahorkai captures the shared angst that paradoxically divides us, rendering us helpless before the haplessness of others. But unlike us, perhaps, Krasznahorkai’s Florian acts anyway, finding his power even as he loses himself, becoming a force without nature and an apocalypse without eschatology. This is not a didactic novel, and it offers none of the comfort that Florian finds in Bach. It is, however, a masterful study in what it means to keep trudging through a world that is always ending but will not end, except, at last, with the relief of a period that finally arrives." — Jacob Brogan in The Washington Post"Laszlo Krasznahorkai’s Herscht 07769 is a maximalist black comedy in the form of a single uninterrupted sentence (and Ottilie Mulzet’s translation from the Hungarian is a feat), reminiscent of postwar novels from Eastern Europe like Bohumil Hrabal’s Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age. Both novels represent an attempt to resuscitate a bygone era of literary history, but in this post-historical era, the future is itself an antique concept." — Stephen Piccarella in The Baffler

♦ Shortlisted for the 2025 EBRD Literature Prize♦ Finalist for the 2024 National Book Critics Circle Gregg Barrios Book in Translation Prize ♦ Finalist for the Cercador Award, 2024♦ Washington Post 50 notable works of fiction from 2024"In a single sentence that sprawls out over 400 pages, Krasznahorkai tells the story of a Bach-obsessed gentle giant who unknowingly consorts with a gang of neo-Nazis. The surprisingly readable results offer a timely warning about our impotent slide into authoritarianism."♦ The TLS Books of the Year 2024"There simply isn't another writer like László Krasznahorkai, whose Herscht 07769 (Tuskar Rock), translated from the Hungarian by Ottilie Mulzet, is a single sentence amounting to some 400 pages and telling of Florian, a man who is convinced that all physical matter is on the brink of extinction and who initiates a one-sided conversation with Angela Merkel in a vain attempt to stave off apocalypse, all the while living at the beck and call of 'the Boss', the head of a neo-Nazi gang and a zealous devotee of Bach who has become maddened by attacks on statues of the composer throughout Thurginia - the plot, if you can call it that, so far out on the horizon of realism, with characters whose passions and obsessions are exposed so nakedly, that the novel, but the best of Krasznahorkai, takes on the cast of a sinister fable, it's sentence rushing headlong over a cliff, into a void." — Michael Lapointe"The form is demanding (it’s a single 400-page sentence), but Krasznahorkai’s latest is worth every moment of concentration. At the center of the narrative is Florian Herscht, a gentle giant with an intellectual disability who’s being exploited by a neo-Nazi gang leader. What makes this so exciting and satisfying is the author’s clear-eyed and open-hearted exploration of conspiracy thinking and nationalism, and the divisiveness they fuel."Editor's Choice: Seven New Books We Recommend This Week: "The protagonist of this feverish novel, a hulking man-child living in what used to be East Germany, writes pleading letters to Chancellor Angela Merkel imploring her to use her physics background to prevent a pending apocalypse. Beneath that improbable surface, the novel — which unspools in a single breathless sentence, rife with detours and digressions ably navigated by the translator Ottilie Mulzet." — The New York Times"In the abstract, his artistry may sound forbidding to all but the most devoted lovers of the European art novel. In concrete terms, though, Krasznahorkai’s work offers, to a degree rare in contemporary life, one of the central pleasures of fiction: an encounter with the otherness of other people. He’s a universalist cut loose from the shibboleths of humanism. And if 'Herscht 07769' doesn’t quite reach the heights of his masterpieces — 'The Melancholy of Resistance,' 'War & War' and 'Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming' — it may be the most accessible entry point so far to his visionary oeuvre.”—Garth Risk Hallberg in The New York Times" In a long book with only one terminal punctuation mark, not easy to read but graced by a certain poetry, Krasznahorkai allegorizes globalism and nationalism, gets in digs at complacent burgers and ardent environmentalists, and illustrates, through Florian and other characters, how thinly the veneer of civilization lies atop a thick crust of savagery. Brilliant, like all of Krasznahorkai’s books—and just as challenging, though well worth the effort required.”—Kirkus Reviews"'Apocalypse is the natural state of life,' Florian writes to Merkel, a line that doubles as an artist statement for Krasznahorkai’s brilliantly cacophonous novel, which conveys the sense that the end is already here, and that the trappings of civilization are easier to scrape away than paint from stone. This stands with Krasznahorkai’s best work.”—Publishers Weekly, starred review"The novel is over 400 pages but contains only one sentence, brilliantly translated by Ottilie Mulzet. It flows on and on in rhythmic phrases that absorb and enchant, sweeping us into a river of prose that is as captivating as it is disturbing. Herscht 07769 is a powerful portrayal of the dangers of nationalism and how fear rots a society from inside. It’s also a shattering story of violence and revenge and one person’s valiant if doomed attempts to change the world." — Rebecca Hussey, Judges’ appreciations for the six finalists of the National Book Critics Circle’s Gregg Barrios Book in Translation Prize"The syntactical flow is so potent it can rely on a simple comma for a major transition; it slips in and out of dialogue or violence, those more jagged rhythms, without losing cumulative effect. Such a style isn’t unique to Krasznahorkai (see William Gaddis, The Recognitions), but few writers have carried on so undaunted or shown such dexterity. Amid vast blocks of unbroken prose, action and desire develop with remarkable clarity, and there’s no mistaking the tonal shifts into threat or seduction⎯subtleties that, in English, bear out the heroic efforts of his translators, the latest the award-winning Ottilie Mulzet." — John Domini in Brooklyn Rail"... it’s like parting a curtain and stepping into a slow tornado of images, ideas, thought patterns whirling and elliptical, ever transforming, misdirecting, stuttering, stumbling through cascading potential pathways jutting out in every direction—it’s like stepping into a river and becoming a paper boat, floating down a river that commands your movement with its currents, here poetically rendered by Ottilie Mulzet’s translation, and Krasznahorkai is that river, conducting the movement of attention, the direction of the sentence, the meticulously plotted introductions of information, character, setting, conflicts”—Christopher Riggs in Asymptote"And yet that book — “Herscht 07769,” by the Hungarian genius László Krasznahorkai — is neitheran experimental stunt nor a pretentious folly. It is, instead, an urgent depiction of ourglobal social and political crises, rendering our impotent slide into authoritarianism withcompassionate clarity. It is also a book whose timeliness derives precisely from the wayits unusual style disrupts the ordinary literary mechanics of time... In all of this, Krasznahorkai captures the shared angst that paradoxically divides us, rendering us helpless before the haplessness of others. But unlike us, perhaps, Krasznahorkai’s Florian acts anyway, finding his power even as he loses himself, becoming a force without nature and an apocalypse without eschatology. This is not a didactic novel, and it offers none of the comfort that Florian finds in Bach. It is, however, a masterful study in what it means to keep trudging through a world that is always ending but will not end, except, at last, with the relief of a period that finally arrives." — Jacob Brogan in The Washington Post"Laszlo Krasznahorkai’s Herscht 07769 is a maximalist black comedy in the form of a single uninterrupted sentence (and Ottilie Mulzet’s translation from the Hungarian is a feat), reminiscent of postwar novels from Eastern Europe like Bohumil Hrabal’s Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age. Both novels represent an attempt to resuscitate a bygone era of literary history, but in this post-historical era, the future is itself an antique concept." — Stephen Piccarella in The Baffler "The lecturer in Seiobo There Below tells his students that ‘the Baroque is the artwork of pain, for deep down in the Baroque there is deep pain ... the Baroque is the art form of death, the art form that tells us that we must die.’ How Krasznahorkian, to suggest that art’s pinnacle is our nadir. When Merkel’s reply to Florian finally arrives, Herr Volkenant – who has just buried Jessica, her body mangled in a car crash – must put it in a box labelled ‘undeliverable’. Florian, still on the run, will probably never read it. But if that undeliverable box is also the black box of quantum physics, then who can say? Florian’s neighbour Frau Hopf understands that ‘as long as people are alive, they hope.’ Does this double for readers, who have two realms to hope for? Perhaps it’s Krasznahorkai’s ultimate cruel irony.”—Ange Mlinko in the London Review of Books"If I only mention now that the entire novel takes place over a single sentence, it is partly because this has become such a trademark of Krasznahorkai’s work as to seem unremarkable; but the greater reason is that, in Ottilie Mulzet’s sinuous translation, being confined in this unceasing prose is an ease, not an impediment. Within this flow the novel’s shifts between the perspectives of Kana’s inhabitants create a remarkable sense of polyphony.”—Nick Holdstock in The Times Literary Supplement"Herscht 07769 is a work of genius, astonishingly well translated by Ottilie Mulzet: I can only imagine the labour and dedication involved in capturing the rhythm of Krasznahorkai's clauses, their strange and captivating music.”— (5 stars) Luke Kennard in The Telegraph"There is every reason to be daunted by Krasznahorkai’s latest work... It is 406 pages long, comprises a single sentence (pedantically one might say that it has no full stops), and the epigraph succinctly encapsulates Krasznahorkai’s worldview: 'Hope is a mistake'. Yet what a humane, compelling, intriguing novel it is, and remarkably it is perhaps less oblique and eccentric than his previous works. If you are going to commence on Krasznahorkai, this might well be the book. It takes no more than a few pages to tune into the style, and the reader quickly picks up when the flow is going to pivot. The free-floating nature of it means Krasznahorkai can create some extraordinary effects, like narrating the very moment of a death.”— Stuart Kelly in The Scotsman"Told in a continuous sentence of 400 pages the novel’s central section is less like the Bach Cantatas that enrapture Florian and more like Ravel’s Bolero, with thematic material recurring incessantly. The plausibility of what occurs is stretched, too, especially with coincidences, as the author himself realises, by giving Florian the humorous aside that 'such coincidence only happens in novels, but this isn’t a novel'. Yet, this is a novel. A novel that reaches for wonder and wisdom. A paean to depth and meaning amid violence and death. A novel that finds its greatest poignancy in the blinding of two beautiful wolves.”— Declan O'Driscoll in The Irish Times"Herscht 07769 features the usual idiosyncratic LK style and rhythm, and Mulzet, who has translated several of his works into English now, is well in her stride here, yet in many ways, this one is a more accessible novel than many others. The setting appears more grounded in the real world (even if the occasional appearance by wolves and eagles might suggest otherwise), and while much, as ever, is made of the book being ‘one sentence’, that’s not really the case. The writer simply moves from one scene to another with commas, pulling the reader along without allowing them the chance to pause. The effect is to make the novel a page-turner, with the reader racing along to see what happens next.”— Tony's Reading List

"The lecturer in Seiobo There Below tells his students that ‘the Baroque is the artwork of pain, for deep down in the Baroque there is deep pain ... the Baroque is the art form of death, the art form that tells us that we must die.’ How Krasznahorkian, to suggest that art’s pinnacle is our nadir. When Merkel’s reply to Florian finally arrives, Herr Volkenant – who has just buried Jessica, her body mangled in a car crash – must put it in a box labelled ‘undeliverable’. Florian, still on the run, will probably never read it. But if that undeliverable box is also the black box of quantum physics, then who can say? Florian’s neighbour Frau Hopf understands that ‘as long as people are alive, they hope.’ Does this double for readers, who have two realms to hope for? Perhaps it’s Krasznahorkai’s ultimate cruel irony.”—Ange Mlinko in the London Review of Books"If I only mention now that the entire novel takes place over a single sentence, it is partly because this has become such a trademark of Krasznahorkai’s work as to seem unremarkable; but the greater reason is that, in Ottilie Mulzet’s sinuous translation, being confined in this unceasing prose is an ease, not an impediment. Within this flow the novel’s shifts between the perspectives of Kana’s inhabitants create a remarkable sense of polyphony.”—Nick Holdstock in The Times Literary Supplement"Herscht 07769 is a work of genius, astonishingly well translated by Ottilie Mulzet: I can only imagine the labour and dedication involved in capturing the rhythm of Krasznahorkai's clauses, their strange and captivating music.”— (5 stars) Luke Kennard in The Telegraph"There is every reason to be daunted by Krasznahorkai’s latest work... It is 406 pages long, comprises a single sentence (pedantically one might say that it has no full stops), and the epigraph succinctly encapsulates Krasznahorkai’s worldview: 'Hope is a mistake'. Yet what a humane, compelling, intriguing novel it is, and remarkably it is perhaps less oblique and eccentric than his previous works. If you are going to commence on Krasznahorkai, this might well be the book. It takes no more than a few pages to tune into the style, and the reader quickly picks up when the flow is going to pivot. The free-floating nature of it means Krasznahorkai can create some extraordinary effects, like narrating the very moment of a death.”— Stuart Kelly in The Scotsman"Told in a continuous sentence of 400 pages the novel’s central section is less like the Bach Cantatas that enrapture Florian and more like Ravel’s Bolero, with thematic material recurring incessantly. The plausibility of what occurs is stretched, too, especially with coincidences, as the author himself realises, by giving Florian the humorous aside that 'such coincidence only happens in novels, but this isn’t a novel'. Yet, this is a novel. A novel that reaches for wonder and wisdom. A paean to depth and meaning amid violence and death. A novel that finds its greatest poignancy in the blinding of two beautiful wolves.”— Declan O'Driscoll in The Irish Times"Herscht 07769 features the usual idiosyncratic LK style and rhythm, and Mulzet, who has translated several of his works into English now, is well in her stride here, yet in many ways, this one is a more accessible novel than many others. The setting appears more grounded in the real world (even if the occasional appearance by wolves and eagles might suggest otherwise), and while much, as ever, is made of the book being ‘one sentence’, that’s not really the case. The writer simply moves from one scene to another with commas, pulling the reader along without allowing them the chance to pause. The effect is to make the novel a page-turner, with the reader racing along to see what happens next.”— Tony's Reading List "Kafka’s tortured relationship with his father is well known to the author’s readers, but Borbély adds to the lore by exploring the limits of how much anyone can understand another, whether a father and son, or a reader and writer, as Mulzet suggests in an illuminating afterword about Borbély’s long-held identification with Kafka. Kafka fans will enjoy this.”—Publishers Weekly"This visuality, a distinctive feature of the book, persists throughout Borbély’s prose and lends to its immense, near compelling readability, even if no linear narrative may be found. Each fragment is enriched with a language both dream-like and cinematic, and Ottilie Mulzet’s fluid, almost taut, tightly woven translation results in a seamless composition, with no awkward phrasing or out-of-place line to be found.”—Urooj, Asymptote, "What's New in Translation"

"Kafka’s tortured relationship with his father is well known to the author’s readers, but Borbély adds to the lore by exploring the limits of how much anyone can understand another, whether a father and son, or a reader and writer, as Mulzet suggests in an illuminating afterword about Borbély’s long-held identification with Kafka. Kafka fans will enjoy this.”—Publishers Weekly"This visuality, a distinctive feature of the book, persists throughout Borbély’s prose and lends to its immense, near compelling readability, even if no linear narrative may be found. Each fragment is enriched with a language both dream-like and cinematic, and Ottilie Mulzet’s fluid, almost taut, tightly woven translation results in a seamless composition, with no awkward phrasing or out-of-place line to be found.”—Urooj, Asymptote, "What's New in Translation" "The Story of Emma K. sucks you in, whirls you around, and then, much like Emma K. herself, spits you out into a world that is complex and harsh, yet compelling and seductive—bounded by forces beyond our control, but in which we must inevitably take part. Like life itself, this collection will at times leave you dazed and confused, but craving more.’—Rachel Stanyon, Asymptote Journal"The fiction of Zsolt Láng inhabits a slippery space where time, genre, and realities shift and bend, where history shapes and distorts the landscape, and where characters are driven by conflicted passions and paranoias. Think of Flann O’Brien with a side order of Beckett, born and raised in Transylvania, charting his own course to become one of the premier postmodernist Hungarian language writers of our time and you have a hint of what you might find in Láng. And now, for the first time, we can sample that strange brew in English through the stories collected in The Birth of Emma K., translated by Owen Good and Ottilie Mulzet, but, be prepared, it is a delightfully odd journey during which one can lose one’s bearings from time to time.’—Joseph Schreiber, Rough Ghosts"There is often a profound awareness of uncertainty within Hungarian fiction. Whether it be parents who are prepared to miss their beloved daughter when she leaves home for the first time only to discover they prefer her to be gone, poor villagers who learn the guiding myth of their existence is as decrepit as they are, or newlyweds deeply in love who grow inexorably apart during their honeymoon, the theme seems clear – nothing is ever what it seems, and one should accept this truth as quickly as possible. The stories in The Birth Of Emma K., Zsolt Láng’s English language debut, are not merely embedded in this tradition. They take it to another dimension.’—John Riley, Litro Magazine

"The Story of Emma K. sucks you in, whirls you around, and then, much like Emma K. herself, spits you out into a world that is complex and harsh, yet compelling and seductive—bounded by forces beyond our control, but in which we must inevitably take part. Like life itself, this collection will at times leave you dazed and confused, but craving more.’—Rachel Stanyon, Asymptote Journal"The fiction of Zsolt Láng inhabits a slippery space where time, genre, and realities shift and bend, where history shapes and distorts the landscape, and where characters are driven by conflicted passions and paranoias. Think of Flann O’Brien with a side order of Beckett, born and raised in Transylvania, charting his own course to become one of the premier postmodernist Hungarian language writers of our time and you have a hint of what you might find in Láng. And now, for the first time, we can sample that strange brew in English through the stories collected in The Birth of Emma K., translated by Owen Good and Ottilie Mulzet, but, be prepared, it is a delightfully odd journey during which one can lose one’s bearings from time to time.’—Joseph Schreiber, Rough Ghosts"There is often a profound awareness of uncertainty within Hungarian fiction. Whether it be parents who are prepared to miss their beloved daughter when she leaves home for the first time only to discover they prefer her to be gone, poor villagers who learn the guiding myth of their existence is as decrepit as they are, or newlyweds deeply in love who grow inexorably apart during their honeymoon, the theme seems clear – nothing is ever what it seems, and one should accept this truth as quickly as possible. The stories in The Birth Of Emma K., Zsolt Láng’s English language debut, are not merely embedded in this tradition. They take it to another dimension.’—John Riley, Litro Magazine "The grandson of Prince Genji wanders an ancient monastery in Kyoto. He seeks a fabled garden whose beauty promises a kind of sublimity: 'Whoever stood there and looked at this would never want to utter even a single word; such a person would simply look, and be silent.' The novella, gorgeously translated by Ottilie Mulzet, comprises a catalog of the wanderer’s findings: architectural ephemera, silk scrolls, rooms within rooms, traces of paintings, sake glasses and illustrated magazines... Amid this patient, beguiling inventory, intimations of a fallen world persist. A slovenly retinue in European dress pursues the prince’s grandson through the city. Thirteen withered goldfish are nailed through their eyes to a wooden hut. A grievously wounded dog climbs a hill with terrifying single-mindedness. These instances of violence underscore the precarity of Krasznahorkaian transcendence, which is nearly always contiguous with apocalypse.”—Dustin Illingworth, The New York Times"If this riff on artistic creation resonates, László Krasznahorkai’s slight, almost static novella A Mountain to the North, a Lake to the South, Paths to the West, a River to the East may speak to you as it did to me, slowly revealing itself as a meditation not only on Buddhism and the fragility of life, but also on writing, on the creation of art, and on aesthetic fulfillment in general, a journey that can be exhausting, elusive, consuming, frustrating, and ultimately futile. Ottilie Mulzet’s characteristically wondrous translation is the ninth of Krasznahorkai’s works to appear in English over the past decade, and while the book was originally published in Hungarian in 2003, it still feels like a fitting coda to the Man Booker International winner’s remarkable oeuvre.”—Cory Oldweiler, The Los Angeles Review of Books"The mistake is in believing that such a hermitage can be found. A garden, a library, a tower — they are all chimeras of the mind, as empty as the space that encloses them. For a box built in the abyss shelters nothing. All of Krasznahorkai’s characters are desperate for some asylum, to gain access, unaware that they are already inside that which they wish to enter. There can never be any arrival, only pursuit.”—Jared Marcel Pollen, Astra Magazine"When you open one of [Krasznahorkai's] novels, it can be a shock to see no ragged margins, just a sheer bank of language, inexorable as a funeral stela. But once you proceed down the winding path of a character’s obsessive thoughts, you have no choice but to read on with a similar compulsion... This is a book preoccupied with infinity. Krasznahorkai’s project, it seems, is to thwart the passing of time through a program of looking. When a person’s eye lingers, the moment swells; to describe something in excess is therefore a hedge against death. At first, Krasznahorkai’s incantations seduce us. Yes, we think, time is a concertina. Everything is always. And yet, deep within the monastery, Krasznahorkai plants a counterpoint to this premise..”—Laura Preston, The Believer Magazine"Despite being the only real character, the grandson of Prince Genji is a marginal figure because all of humanity is marginal in the grand scheme of things. Krasznahorkai reminds us that humanity’s existence was a natural result of possibility and probability – we had and have little choice in the matter. Yet, A Mountain to the North never revels in nihilism. Meaning is something we search for, just like the grandson of Prince Genji searches for his garden. We’re small, but we’re no less important than any of the billions of years that preceded us. Krasznahorkai wants us to get comfortable with this idea, because only then can we, 'begin to see that there [is] only the whole, and no details.'”—Dylan Cook, Cleaver Magazine

"The grandson of Prince Genji wanders an ancient monastery in Kyoto. He seeks a fabled garden whose beauty promises a kind of sublimity: 'Whoever stood there and looked at this would never want to utter even a single word; such a person would simply look, and be silent.' The novella, gorgeously translated by Ottilie Mulzet, comprises a catalog of the wanderer’s findings: architectural ephemera, silk scrolls, rooms within rooms, traces of paintings, sake glasses and illustrated magazines... Amid this patient, beguiling inventory, intimations of a fallen world persist. A slovenly retinue in European dress pursues the prince’s grandson through the city. Thirteen withered goldfish are nailed through their eyes to a wooden hut. A grievously wounded dog climbs a hill with terrifying single-mindedness. These instances of violence underscore the precarity of Krasznahorkaian transcendence, which is nearly always contiguous with apocalypse.”—Dustin Illingworth, The New York Times"If this riff on artistic creation resonates, László Krasznahorkai’s slight, almost static novella A Mountain to the North, a Lake to the South, Paths to the West, a River to the East may speak to you as it did to me, slowly revealing itself as a meditation not only on Buddhism and the fragility of life, but also on writing, on the creation of art, and on aesthetic fulfillment in general, a journey that can be exhausting, elusive, consuming, frustrating, and ultimately futile. Ottilie Mulzet’s characteristically wondrous translation is the ninth of Krasznahorkai’s works to appear in English over the past decade, and while the book was originally published in Hungarian in 2003, it still feels like a fitting coda to the Man Booker International winner’s remarkable oeuvre.”—Cory Oldweiler, The Los Angeles Review of Books"The mistake is in believing that such a hermitage can be found. A garden, a library, a tower — they are all chimeras of the mind, as empty as the space that encloses them. For a box built in the abyss shelters nothing. All of Krasznahorkai’s characters are desperate for some asylum, to gain access, unaware that they are already inside that which they wish to enter. There can never be any arrival, only pursuit.”—Jared Marcel Pollen, Astra Magazine"When you open one of [Krasznahorkai's] novels, it can be a shock to see no ragged margins, just a sheer bank of language, inexorable as a funeral stela. But once you proceed down the winding path of a character’s obsessive thoughts, you have no choice but to read on with a similar compulsion... This is a book preoccupied with infinity. Krasznahorkai’s project, it seems, is to thwart the passing of time through a program of looking. When a person’s eye lingers, the moment swells; to describe something in excess is therefore a hedge against death. At first, Krasznahorkai’s incantations seduce us. Yes, we think, time is a concertina. Everything is always. And yet, deep within the monastery, Krasznahorkai plants a counterpoint to this premise..”—Laura Preston, The Believer Magazine"Despite being the only real character, the grandson of Prince Genji is a marginal figure because all of humanity is marginal in the grand scheme of things. Krasznahorkai reminds us that humanity’s existence was a natural result of possibility and probability – we had and have little choice in the matter. Yet, A Mountain to the North never revels in nihilism. Meaning is something we search for, just like the grandson of Prince Genji searches for his garden. We’re small, but we’re no less important than any of the billions of years that preceded us. Krasznahorkai wants us to get comfortable with this idea, because only then can we, 'begin to see that there [is] only the whole, and no details.'”—Dylan Cook, Cleaver Magazine "It is in the telling of this apparently simple story that the immense appeal of this beautiful novel lies. At one point, Krasznahorkai speaks of 'the strength of simplicity’s enchantment' and, through Mulzet’s exceptional work, we can appreciate the enchantment of language that is attentive to precise details and which conjures the serenity that is sought throughout. The author makes his intentions clear when he says that, 'this tradition was built upon observation, repetition, and the veneration of the inner order of nature and the nature of things, and that neither the meaning nor the purity of this tradition could ever be brought into question'.”—Declan O'Driscoll, The Irish Times, "January’s best new translated fiction""Krasznahorkai and Mulzet have both paid careful attention to prosody, so that we may read this novel in accordance with the author’s intentions. Although full stops are absent, the sentences bristle with punctuation: commas and semi-colons keep the flow measured, meditative, additive, rolling calmly on, on, on. In a word, take it slow. And it works: a calm descends over you, and the mind quickly adjusts and resigns itself to the inexorable swell of information... Tranquillity curdling into boredom is the chief danger here, and one of the impressive achievements of A Mountain to the North is how well it maintains its reverie—how dull it isn’t. Credit here is due to author and translator in equal measure; sentences of this length and delicateness pose an extreme technical challenge to the translator, one that is made harder still by certain grammatical disparities between Hungarian and English—the largest of which being the agglutinative nature of Hungarian, which can accommodate long sentences more easily than English can. Nevertheless, Ottilie Mulzet succeeds, and her sentences mesmerise. There are occasional and possibly inescapable moments of ponderousness—a stubby clause, a qualification too many—but Mulzet renders the formidable syntax with great skill and care. Very rarely do you yearn for one of these sentences to end.”—Matthew Redman, Asymptote, "What's New in Translation""In Ottilie Mulzet’s translation, the prose reaffirms both the architectural complexities of the monastery and their precise obedience to a system. It is a system of thought, 'difficult to perceive, or completely nontransparent to the everyday eye'. In the monastery, it always prevails in the perfect alignment of content to structure; perhaps in the world, too... Eventually, you see that you’ve been treated to a metaphysical mystery story, and that the mystery has all along been both secreted and revealed in the precision and care and sleight-of-hand with which László Krasznahorkai wrote his novel.”—M. John Harrison, The Times Literary Supplement"The prose, at least, persists. Ottilie Mulzet has laid into English Krasznahorkai’s familiar style: those long, sinuous sentences, which loop forward from comma to comma, stepping back to revise a detail, till they suddenly reach an end. The watchword is always control: a whole chapter can be filled by the lifting of a breeze or the chime of a bell. This is fiction as hypnosis, and if opacity haunts A Mountain…, it is not clear it would disperse on a second reading, or beyond. And yet – for all your doubts and questions – there is so much beauty in this patch of serenity.”—Cal Revely-Calder, Telegraph"Retaining all the intricacy and tortuousness of Krasznahorkai’s distinctive prose, the novella, now rendered in Ottilie Mulzet’s fine translation, is imbued with precision that can be glorious, but also, at times, profoundly taxing. Objects and actions are described with such intensely analytical detail that the reader is often forced to pause, go back and reread passages several times over just to parse them.This characteristic postmodern artificiality makes indisputable demands on the reader, but there is significant reward for those willing to take up the challenge."—Bryan Karetnyk, The Financial Times, "The Best Books of the Week""Originally published in 2003, now available in a discerning translation by Ottilie Mulzet, A Mountain to the North, A Lake to The South, Paths to the West, A River to the East is a enveloping work that is part existential meditation and mystery, part exposition of the design and construction of Buddhist monasteries, part fantastical geological and botanical visualization and much more. It exists and unfolds in a magical realm of its own, suspended on meticulous details of Japanese Buddhist tradition, practice and design, but raising a much more pragmatic question: what is more important, the quest or its successful completion?"—Joseph Schreiber, Rough Ghosts

"It is in the telling of this apparently simple story that the immense appeal of this beautiful novel lies. At one point, Krasznahorkai speaks of 'the strength of simplicity’s enchantment' and, through Mulzet’s exceptional work, we can appreciate the enchantment of language that is attentive to precise details and which conjures the serenity that is sought throughout. The author makes his intentions clear when he says that, 'this tradition was built upon observation, repetition, and the veneration of the inner order of nature and the nature of things, and that neither the meaning nor the purity of this tradition could ever be brought into question'.”—Declan O'Driscoll, The Irish Times, "January’s best new translated fiction""Krasznahorkai and Mulzet have both paid careful attention to prosody, so that we may read this novel in accordance with the author’s intentions. Although full stops are absent, the sentences bristle with punctuation: commas and semi-colons keep the flow measured, meditative, additive, rolling calmly on, on, on. In a word, take it slow. And it works: a calm descends over you, and the mind quickly adjusts and resigns itself to the inexorable swell of information... Tranquillity curdling into boredom is the chief danger here, and one of the impressive achievements of A Mountain to the North is how well it maintains its reverie—how dull it isn’t. Credit here is due to author and translator in equal measure; sentences of this length and delicateness pose an extreme technical challenge to the translator, one that is made harder still by certain grammatical disparities between Hungarian and English—the largest of which being the agglutinative nature of Hungarian, which can accommodate long sentences more easily than English can. Nevertheless, Ottilie Mulzet succeeds, and her sentences mesmerise. There are occasional and possibly inescapable moments of ponderousness—a stubby clause, a qualification too many—but Mulzet renders the formidable syntax with great skill and care. Very rarely do you yearn for one of these sentences to end.”—Matthew Redman, Asymptote, "What's New in Translation""In Ottilie Mulzet’s translation, the prose reaffirms both the architectural complexities of the monastery and their precise obedience to a system. It is a system of thought, 'difficult to perceive, or completely nontransparent to the everyday eye'. In the monastery, it always prevails in the perfect alignment of content to structure; perhaps in the world, too... Eventually, you see that you’ve been treated to a metaphysical mystery story, and that the mystery has all along been both secreted and revealed in the precision and care and sleight-of-hand with which László Krasznahorkai wrote his novel.”—M. John Harrison, The Times Literary Supplement"The prose, at least, persists. Ottilie Mulzet has laid into English Krasznahorkai’s familiar style: those long, sinuous sentences, which loop forward from comma to comma, stepping back to revise a detail, till they suddenly reach an end. The watchword is always control: a whole chapter can be filled by the lifting of a breeze or the chime of a bell. This is fiction as hypnosis, and if opacity haunts A Mountain…, it is not clear it would disperse on a second reading, or beyond. And yet – for all your doubts and questions – there is so much beauty in this patch of serenity.”—Cal Revely-Calder, Telegraph"Retaining all the intricacy and tortuousness of Krasznahorkai’s distinctive prose, the novella, now rendered in Ottilie Mulzet’s fine translation, is imbued with precision that can be glorious, but also, at times, profoundly taxing. Objects and actions are described with such intensely analytical detail that the reader is often forced to pause, go back and reread passages several times over just to parse them.This characteristic postmodern artificiality makes indisputable demands on the reader, but there is significant reward for those willing to take up the challenge."—Bryan Karetnyk, The Financial Times, "The Best Books of the Week""Originally published in 2003, now available in a discerning translation by Ottilie Mulzet, A Mountain to the North, A Lake to The South, Paths to the West, A River to the East is a enveloping work that is part existential meditation and mystery, part exposition of the design and construction of Buddhist monasteries, part fantastical geological and botanical visualization and much more. It exists and unfolds in a magical realm of its own, suspended on meticulous details of Japanese Buddhist tradition, practice and design, but raising a much more pragmatic question: what is more important, the quest or its successful completion?"—Joseph Schreiber, Rough Ghosts "The narrator is an angel who had lived the lives – and now revives the voices — of two characters separated by two centuries of grim and tragic history. First, there is Johann Klarfeld, born in 1723, whose picaresque adventures find him traveling through Germany, first fighting for the German army and then the French army. Ultimately, he winds up in The Hague, working as a painter’s assistant and falls in love with his daughter. She has a secret. The second voiced character is a Hungarian girl, Berta Józsa, born in 1943. The angel speaks in its own voice: 'I live in that ruinous interstice caused by the spillage of times, of which most people know only the two shores: yesterday and today, life and death; in vain are they without possessions on this earth. I, however, recognize neither one … Everything is now.' In this way, Schein establishes his tone: mordant, candid, disillusioned but undeterred...

"The narrator is an angel who had lived the lives – and now revives the voices — of two characters separated by two centuries of grim and tragic history. First, there is Johann Klarfeld, born in 1723, whose picaresque adventures find him traveling through Germany, first fighting for the German army and then the French army. Ultimately, he winds up in The Hague, working as a painter’s assistant and falls in love with his daughter. She has a secret. The second voiced character is a Hungarian girl, Berta Józsa, born in 1943. The angel speaks in its own voice: 'I live in that ruinous interstice caused by the spillage of times, of which most people know only the two shores: yesterday and today, life and death; in vain are they without possessions on this earth. I, however, recognize neither one … Everything is now.' In this way, Schein establishes his tone: mordant, candid, disillusioned but undeterred...  "...Ottilie Mulzet, the primary translator of Borbély’s work... has been a persistent advocate for the publication of Borbély’s work outside of Hungary... Her renderings into English, of this collection and of other works, are remarkable.This recent collection is an encounter with a rich, unsettling mythology. In the first few lines of nearly every poem, Borbély turns our attention to the “gods” of the world he is creating. In a way, it feels as if he is summoning them, as one does with a muse. The visual experience of the collection - with numbered sections - further connects the series of poems to the tradition of epic poetry.”—Christie Goodwin, HLO"I am staggered by In a Bucolic Land. In long, wending lines, the poems present many of the same scenes and characters as Borbély’s novel, but differently paced and framed: the world of his childhood—a savagely poor rural village, still scarred by World War II, by Nazi and Soviet violence, by its own ingrown anti-Semitism. Animals are tortured, people are cast off, a cow wanders into a church and sniffs at an angel’s face. A Jewish house is ‘vacant.’ Somehow, the child survives and grows up to become the poet who remembers. The book ends in desolation and suicidal temptation. The poems both ‘despise’ language and testify to a powerful faith: ‘Because speech contains form. Therefore it is immortal.’”—Rosanna Warren, Book Recommendations from Our Former Guest Editors, Ploughshares, Spring 2022, No. 151 "Borbély’s poetry in Mulzet’s translation reveals this seamless interweaving of the local and the global among gods and cows and men. Mulzet’s translation of Borbély’s poetry is careful and precise, mediating across languages and worlds to offer a version of Túrricse and rural Hungary that is both accessible and particular. Mulzet does not shy away from the challenge of translating life in Borbély’s hometown village to an English-speaking audience likely unfamiliar with both the minutiae of day-to-day life on a collective farm and the broader history of Eastern Europe in the 20th century in general. And it is in these moments of particularity when the feat of this translation is most strongly laid bare."—Alina Bessenyey Williams in Hopscotch Translation"Shadowing everything in this final collection by the eminent Hungarian poet Szilárd Borbély (1963–2014) is the central trauma of Borbély’s life, the murder of his mother during a brutal home invasion and the breakdown of his father, which led to Borbély’s own posttraumatic depression and—years later—suicide. If Borbély himself could not defend against death, the idyllic, philosophically minded poetry of In a Bucolic Land, translated lucidly by Ottilie Mulzet, lends enduring form to the ashes of affliction."—David Woo on the Harriet Books blog, Poetry Foundation"Gloriously aphoristic lines like “All things / speak to us, from the End, about the / helplessness of the Beginning,” which another lyric poet might rightfully draw attention to, are unselfconsciously tucked away in these drawn-out meditations."—Maya C. Popa, The Poet's Nightstand (the Poetry Society of America)

"...Ottilie Mulzet, the primary translator of Borbély’s work... has been a persistent advocate for the publication of Borbély’s work outside of Hungary... Her renderings into English, of this collection and of other works, are remarkable.This recent collection is an encounter with a rich, unsettling mythology. In the first few lines of nearly every poem, Borbély turns our attention to the “gods” of the world he is creating. In a way, it feels as if he is summoning them, as one does with a muse. The visual experience of the collection - with numbered sections - further connects the series of poems to the tradition of epic poetry.”—Christie Goodwin, HLO"I am staggered by In a Bucolic Land. In long, wending lines, the poems present many of the same scenes and characters as Borbély’s novel, but differently paced and framed: the world of his childhood—a savagely poor rural village, still scarred by World War II, by Nazi and Soviet violence, by its own ingrown anti-Semitism. Animals are tortured, people are cast off, a cow wanders into a church and sniffs at an angel’s face. A Jewish house is ‘vacant.’ Somehow, the child survives and grows up to become the poet who remembers. The book ends in desolation and suicidal temptation. The poems both ‘despise’ language and testify to a powerful faith: ‘Because speech contains form. Therefore it is immortal.’”—Rosanna Warren, Book Recommendations from Our Former Guest Editors, Ploughshares, Spring 2022, No. 151 "Borbély’s poetry in Mulzet’s translation reveals this seamless interweaving of the local and the global among gods and cows and men. Mulzet’s translation of Borbély’s poetry is careful and precise, mediating across languages and worlds to offer a version of Túrricse and rural Hungary that is both accessible and particular. Mulzet does not shy away from the challenge of translating life in Borbély’s hometown village to an English-speaking audience likely unfamiliar with both the minutiae of day-to-day life on a collective farm and the broader history of Eastern Europe in the 20th century in general. And it is in these moments of particularity when the feat of this translation is most strongly laid bare."—Alina Bessenyey Williams in Hopscotch Translation"Shadowing everything in this final collection by the eminent Hungarian poet Szilárd Borbély (1963–2014) is the central trauma of Borbély’s life, the murder of his mother during a brutal home invasion and the breakdown of his father, which led to Borbély’s own posttraumatic depression and—years later—suicide. If Borbély himself could not defend against death, the idyllic, philosophically minded poetry of In a Bucolic Land, translated lucidly by Ottilie Mulzet, lends enduring form to the ashes of affliction."—David Woo on the Harriet Books blog, Poetry Foundation"Gloriously aphoristic lines like “All things / speak to us, from the End, about the / helplessness of the Beginning,” which another lyric poet might rightfully draw attention to, are unselfconsciously tucked away in these drawn-out meditations."—Maya C. Popa, The Poet's Nightstand (the Poetry Society of America) "And The Bone Fire has certainly won acclaim since its original publication in 2014 — it was a finalist for major prizes in France and Italy — before landing in the capable hands of Ottilie Mulzet, the translator who has notably brought us the works of Laszlo Krasznahorkai. The timing is perfect: The novel reaches an American audience at a moment when we’re feeling not only the seismic shifts of historical change, and the hard reckoning after a strongman’s fall, but also the ways magical thinking, conspiracy and rumor seep through the cracks during times of turmoil.

"And The Bone Fire has certainly won acclaim since its original publication in 2014 — it was a finalist for major prizes in France and Italy — before landing in the capable hands of Ottilie Mulzet, the translator who has notably brought us the works of Laszlo Krasznahorkai. The timing is perfect: The novel reaches an American audience at a moment when we’re feeling not only the seismic shifts of historical change, and the hard reckoning after a strongman’s fall, but also the ways magical thinking, conspiracy and rumor seep through the cracks during times of turmoil. "With an immense cast and wide-ranging erudition, this novel, the culmination of a Hungarian master’s career, offers a sweeping view of a contemporary moment that seems deprived of meaning."—The New Yorker, "Briefly Noted""Relentlessly hilarious and shimmeringly dark"—Forrest Gander"This vortex of a novel compares neatly with Dostoevsky and shows Krasznahorkai at the absolute summit of his decades-long project." —Publisher's Weekly"The emotional and psychological realizations Krasznahorkai can evoke are singular and breathtaking."—Seth L. Riley in The Millions"Paradox is at the heart of Krasznahorkai: even as his books seem to affirm meaninglessness, the music of those long, spiraling sentences reflects a great care. Equally, it’s an act of will and of care to read a novel like Wenckheim, the opposite of consuming 'content.' Krasznahorkai’s novels are not something that you halfheartedly acquiesce to after thirty minutes of Netflix scrolling. Content is the killing of time; literature like Krasznahorkai’s helps confront the way meaning and value keep leaking out of that time.."—David Schurman Wallace in The Baffler"Despite Krasznahorkai’s reputation as a writer of dense and exhausting fictions predisposed to apocalyptic ruminations delivered in a frequently abstruse and roundabout fashion, he is also regularly, and quite profoundly, funny ... which, it should be said at the outset, is a unique, frustrating and altogether remarkable achievement."—Adam Rivett in The Monthly

"With an immense cast and wide-ranging erudition, this novel, the culmination of a Hungarian master’s career, offers a sweeping view of a contemporary moment that seems deprived of meaning."—The New Yorker, "Briefly Noted""Relentlessly hilarious and shimmeringly dark"—Forrest Gander"This vortex of a novel compares neatly with Dostoevsky and shows Krasznahorkai at the absolute summit of his decades-long project." —Publisher's Weekly"The emotional and psychological realizations Krasznahorkai can evoke are singular and breathtaking."—Seth L. Riley in The Millions"Paradox is at the heart of Krasznahorkai: even as his books seem to affirm meaninglessness, the music of those long, spiraling sentences reflects a great care. Equally, it’s an act of will and of care to read a novel like Wenckheim, the opposite of consuming 'content.' Krasznahorkai’s novels are not something that you halfheartedly acquiesce to after thirty minutes of Netflix scrolling. Content is the killing of time; literature like Krasznahorkai’s helps confront the way meaning and value keep leaking out of that time.."—David Schurman Wallace in The Baffler"Despite Krasznahorkai’s reputation as a writer of dense and exhausting fictions predisposed to apocalyptic ruminations delivered in a frequently abstruse and roundabout fashion, he is also regularly, and quite profoundly, funny ... which, it should be said at the outset, is a unique, frustrating and altogether remarkable achievement."—Adam Rivett in The Monthly "While the novel energetically pursues Krasznahorkai’s habitual themes – disorder, spiritual drought, the impossibility of meaning in the absence of God – it does so in a tone that glitters with comic detail ... in Ottilie Mulzet’s tirelessly virtuosic translation."—Jane Shilling in the New Stateman"Baron Wenkcheim’s Homecoming is a fitting capstone to Krasznahorkai’s tetralogy, one of the supreme achievements of contemporary literature."—Dustin Illingworth in The Paris Review"Twinkling with dark wit, his dizzyingly torrential sentences (heroically translated by Ottilie Mulzet) forever bait us with the promise of resolution.."—Anthony Cummins in the Guardian"It has a madness and monomania that compel."—Sukhdev Sandhu in the Guardian"Despite, or maybe because of, the depth of insight Krasznahorkai brings to this exceptional and profound novel, intricately translated by Ottilie Mulzet, there are moments of great humour too."—Declan O’Driscoll in the Irish Times

"While the novel energetically pursues Krasznahorkai’s habitual themes – disorder, spiritual drought, the impossibility of meaning in the absence of God – it does so in a tone that glitters with comic detail ... in Ottilie Mulzet’s tirelessly virtuosic translation."—Jane Shilling in the New Stateman"Baron Wenkcheim’s Homecoming is a fitting capstone to Krasznahorkai’s tetralogy, one of the supreme achievements of contemporary literature."—Dustin Illingworth in The Paris Review"Twinkling with dark wit, his dizzyingly torrential sentences (heroically translated by Ottilie Mulzet) forever bait us with the promise of resolution.."—Anthony Cummins in the Guardian"It has a madness and monomania that compel."—Sukhdev Sandhu in the Guardian"Despite, or maybe because of, the depth of insight Krasznahorkai brings to this exceptional and profound novel, intricately translated by Ottilie Mulzet, there are moments of great humour too."—Declan O’Driscoll in the Irish Times "Perceptive meditations on humanity’s need for spiritual nourishment."—Kirkus Reviews“[A] fierce, provoking collection . . . expertly translated by Ottilie Mulzet . . . [Földényi] proves himself a brilliant interpreter of the dark underside of Enlightenment ambition.”—James Wood in The New Yorker“It is precisely Földényi’s approachable style, as well as Ottilie Mulzet’s impeccable translation, that makes this collection easily accessible to scholars and casual readers alike.”—Barbara Halla in Asymptote

"Perceptive meditations on humanity’s need for spiritual nourishment."—Kirkus Reviews“[A] fierce, provoking collection . . . expertly translated by Ottilie Mulzet . . . [Földényi] proves himself a brilliant interpreter of the dark underside of Enlightenment ambition.”—James Wood in The New Yorker“It is precisely Földényi’s approachable style, as well as Ottilie Mulzet’s impeccable translation, that makes this collection easily accessible to scholars and casual readers alike.”—Barbara Halla in Asymptote "The late Hungarian poet Szilárd Borbély’s collection Final Matters is undoubtedly the strangest, most visionary book of verse I’ve read this year."—Robyn Creswell, Words without Borders/The Best Translated Books You Missed in 2019"Translated by Ottilie Mulzet with a rare lyricism and lucidity ... A profoundly disquieting work, which grows stranger and richer with each reading. These poems offer no answers, yet they are a revelation." —Chris Littlewood in the Times Literary Supplement"... Mulzet has undoubtedly brought readers a great gift by bringing these multi-layered poems into English... This is complex, harrowing, and often sublime poetry — a cry against forgetting that deserves to be fully heard." —Aviya Kushner in The Forward"Translated faithfully and beautifully by Ottilie Mulzet... the poetry of Final Matters is a tremendous achievement, and shows that Borbély should be considered not just among the great writers of post-Soviet Europe, but also of contemporary Judaism." —Daniel Kraft in Jewish Currents"Borbély writes mystical lyrics, polytheistic parables and Hasidic sequences too powerful to forget. Like Japan’s wondrous Motoyuki Shibata, Ottilie Mulzet has become a translator with a following. I’m one of those committed to reading anything she takes up." — Forrest Gander"Extraordinary, masterful, and tragic. . . . Ottilie Mulzet is one of the very finest [Hungarian translators]. . . . [Final Matters] as a whole partakes of the darkest and truest apprehensions of humanity. That is its remarkable power, a power that runs through the translations, the work of translation devoting itself to something of great importance and value. Nothing in either contemporary Hungarian or contemporary English compares with it." — George Szirtes, Translation and Literature"In these poems, faith often hangs by a very thin thread, and in the harsh light of suffering and affliction, there are times when it can hardly be seen at all, when it is almost invisible… But it is there. Final Matters is, without doubt, deeply provocative, but it is so in order to shift the debate , to challenge, to ask the difficult questions of any complacent theology or moral philosophy." —Tony Flynn, the High Window"Translated by Mulzet into elegant and tonally astute English ... the poems eventually repudiate all such answers, and it is in this repudiation that the collection’s agonized ingenuity lies." —Carla Baricz in the Los Angeles Review of Books"In Borbély’s case, through a kind of craft that is undeniably in a world of its own, translator Ottilie Mulzet has provided an amazing Hungarian poet with a voice in English, opening a door to a readership that might otherwise never have found out the potency of his words." —Bruce Arlen Wasserman in the New York Journal of Books"One feels the poems are the brilliantly wrought salvages of some perilous descent into the human soul and its primordial encounter with the agonizing mystery of its being ... one can only be grateful for these poems of Szilárd Borbély as they exist now in English in the afterlife of Ottilie Mulzet’s vivid translations." —Daniel Tobin in Literary Matters"Yet [Borbély's] language is calm, unadorned, and his words are shared in such a graceful and understated way, that, despite the melancholy of the writer himself, the reader is left feeling strangely comforted, less alone. This is a wise and generous gift ... Ottilie Mulzet has translated the poems throughout this volume with meticulous clarity and a rare luminosity. Like the poet himself, she uses her gift for language with an elegant restraint which, rather than demonstrating her own virtuosity, simply aims to serve the work itself. " —Barney Bardsley on HLO"For Mulzet’s translation succeeds in echoing the virtuosity and musicality of Borbély’s poetry, her translations are as readable as the original texts. Mulzet is able to reveal what makes Borbély’s poems both dreadful and fascinating. Thus, the selection along with the translator’s afterword can be captivating for also the Anglophone readership that may not be familiar with contemporary Hungarian poetry. " —Anna Branczeiz on Eurolitkrant"The final versions are certainly beautifully done, and for those who (unlike me) can appreciate the originals, the Hungarian text faces the translation, allowing for easy comparison ... There are many great Hungarian writers with work available in English now, and Borbély is another name to add to that list, a writer whose poems often had me coming back for a second (or third) glance."— Tony's Reading List

"The late Hungarian poet Szilárd Borbély’s collection Final Matters is undoubtedly the strangest, most visionary book of verse I’ve read this year."—Robyn Creswell, Words without Borders/The Best Translated Books You Missed in 2019"Translated by Ottilie Mulzet with a rare lyricism and lucidity ... A profoundly disquieting work, which grows stranger and richer with each reading. These poems offer no answers, yet they are a revelation." —Chris Littlewood in the Times Literary Supplement"... Mulzet has undoubtedly brought readers a great gift by bringing these multi-layered poems into English... This is complex, harrowing, and often sublime poetry — a cry against forgetting that deserves to be fully heard." —Aviya Kushner in The Forward"Translated faithfully and beautifully by Ottilie Mulzet... the poetry of Final Matters is a tremendous achievement, and shows that Borbély should be considered not just among the great writers of post-Soviet Europe, but also of contemporary Judaism." —Daniel Kraft in Jewish Currents"Borbély writes mystical lyrics, polytheistic parables and Hasidic sequences too powerful to forget. Like Japan’s wondrous Motoyuki Shibata, Ottilie Mulzet has become a translator with a following. I’m one of those committed to reading anything she takes up." — Forrest Gander"Extraordinary, masterful, and tragic. . . . Ottilie Mulzet is one of the very finest [Hungarian translators]. . . . [Final Matters] as a whole partakes of the darkest and truest apprehensions of humanity. That is its remarkable power, a power that runs through the translations, the work of translation devoting itself to something of great importance and value. Nothing in either contemporary Hungarian or contemporary English compares with it." — George Szirtes, Translation and Literature"In these poems, faith often hangs by a very thin thread, and in the harsh light of suffering and affliction, there are times when it can hardly be seen at all, when it is almost invisible… But it is there. Final Matters is, without doubt, deeply provocative, but it is so in order to shift the debate , to challenge, to ask the difficult questions of any complacent theology or moral philosophy." —Tony Flynn, the High Window"Translated by Mulzet into elegant and tonally astute English ... the poems eventually repudiate all such answers, and it is in this repudiation that the collection’s agonized ingenuity lies." —Carla Baricz in the Los Angeles Review of Books"In Borbély’s case, through a kind of craft that is undeniably in a world of its own, translator Ottilie Mulzet has provided an amazing Hungarian poet with a voice in English, opening a door to a readership that might otherwise never have found out the potency of his words." —Bruce Arlen Wasserman in the New York Journal of Books"One feels the poems are the brilliantly wrought salvages of some perilous descent into the human soul and its primordial encounter with the agonizing mystery of its being ... one can only be grateful for these poems of Szilárd Borbély as they exist now in English in the afterlife of Ottilie Mulzet’s vivid translations." —Daniel Tobin in Literary Matters"Yet [Borbély's] language is calm, unadorned, and his words are shared in such a graceful and understated way, that, despite the melancholy of the writer himself, the reader is left feeling strangely comforted, less alone. This is a wise and generous gift ... Ottilie Mulzet has translated the poems throughout this volume with meticulous clarity and a rare luminosity. Like the poet himself, she uses her gift for language with an elegant restraint which, rather than demonstrating her own virtuosity, simply aims to serve the work itself. " —Barney Bardsley on HLO"For Mulzet’s translation succeeds in echoing the virtuosity and musicality of Borbély’s poetry, her translations are as readable as the original texts. Mulzet is able to reveal what makes Borbély’s poems both dreadful and fascinating. Thus, the selection along with the translator’s afterword can be captivating for also the Anglophone readership that may not be familiar with contemporary Hungarian poetry. " —Anna Branczeiz on Eurolitkrant"The final versions are certainly beautifully done, and for those who (unlike me) can appreciate the originals, the Hungarian text faces the translation, allowing for easy comparison ... There are many great Hungarian writers with work available in English now, and Borbély is another name to add to that list, a writer whose poems often had me coming back for a second (or third) glance."— Tony's Reading List "With impressive subtlety, the translations recreate the playful irony that undercuts the incessant anguish in each story."—Idra Novey in The New York Times Book Review"From the author’s 'uncontrollable impulse to look upon the very axis of the world' emerges a work that shows, undiminished, the complexity of existence—as well as its 'sad and temporarily self-evident goal: oblivion'."—The New Yorker, 'Briefly Noted'"This book breaks all conventions and tests the very limits of language, resulting in a transcendent, astounding experience.."—Publishers Weekly"Hidden within these dense thickets of prose are sublime, often uncanny visions."—Nathaniel Rich in The Atlantic"It is proof of the translators’ skill that Krasznahorkai’s sentences work as well as they do. They aren’t just plausible grammatically — they propel the narrative and give the prose its sense."—Ellen Elias-Bursać in The Arts Fuse"One doesn’t so much read The World Goes On as experience its almost hallucinatory narratives."—Andrew Martino, World Literature Today

"With impressive subtlety, the translations recreate the playful irony that undercuts the incessant anguish in each story."—Idra Novey in The New York Times Book Review"From the author’s 'uncontrollable impulse to look upon the very axis of the world' emerges a work that shows, undiminished, the complexity of existence—as well as its 'sad and temporarily self-evident goal: oblivion'."—The New Yorker, 'Briefly Noted'"This book breaks all conventions and tests the very limits of language, resulting in a transcendent, astounding experience.."—Publishers Weekly"Hidden within these dense thickets of prose are sublime, often uncanny visions."—Nathaniel Rich in The Atlantic"It is proof of the translators’ skill that Krasznahorkai’s sentences work as well as they do. They aren’t just plausible grammatically — they propel the narrative and give the prose its sense."—Ellen Elias-Bursać in The Arts Fuse"One doesn’t so much read The World Goes On as experience its almost hallucinatory narratives."—Andrew Martino, World Literature Today "This collection – a masterpiece of invention, utterly different from everything else – is hugely unsettling and affecting; to meet Krasznahorkai’s characters, to read his breathless, twisting sentences, is to feel altered.."—Claire Kohda Hazelton in The Guardian"Over twenty-one stories in The World Goes On, the author shifts artfully between registers; the book is similar in concept and composition to Seiobo There Below, translated by Ottilie Mulzet, who again proves to be a skilled conduit, this time for five of the tales in the collection."—Eileen Battersby in the Times Literary Supplement"Every story here is enrapturing."—Paddy Kehoe, RTE

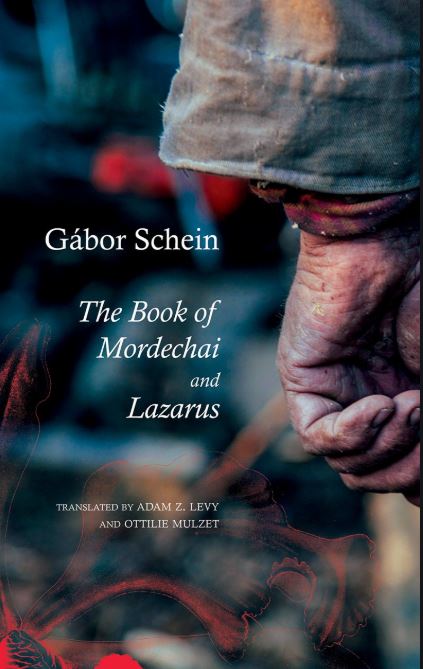

"This collection – a masterpiece of invention, utterly different from everything else – is hugely unsettling and affecting; to meet Krasznahorkai’s characters, to read his breathless, twisting sentences, is to feel altered.."—Claire Kohda Hazelton in The Guardian"Over twenty-one stories in The World Goes On, the author shifts artfully between registers; the book is similar in concept and composition to Seiobo There Below, translated by Ottilie Mulzet, who again proves to be a skilled conduit, this time for five of the tales in the collection."—Eileen Battersby in the Times Literary Supplement"Every story here is enrapturing."—Paddy Kehoe, RTE "Lazarus takes the form of a son writing about his father in express disobedience to the latter’s wishes — an act of love tinged with violence." —Ari R. Hoffmann, The Jewish Book Council"In this two-volume collection, Hungarian writer Gábor Schein melds family drama and biblical teachings with Hungarian history by examining the significant moments of the Holocaust, World War II, and Communist rule. Schein’s fluid narrative style employs descriptive and probing language to capture the search for identity in a convoluted society marred by the unhealed pain of the past." —World Literature Today, "Nota Benes" "The late twentieth century has cast a long shadow and, as the generation who lived through it are reaching old age and leaving us to reckon with a world where the far right are again up to no good – particularly but not solely in Hungary – thoughtful reflections such as The Book of Mordechai and Lazarus are needed more than ever." —J. C. Greenway, Ten Million Hardbacks